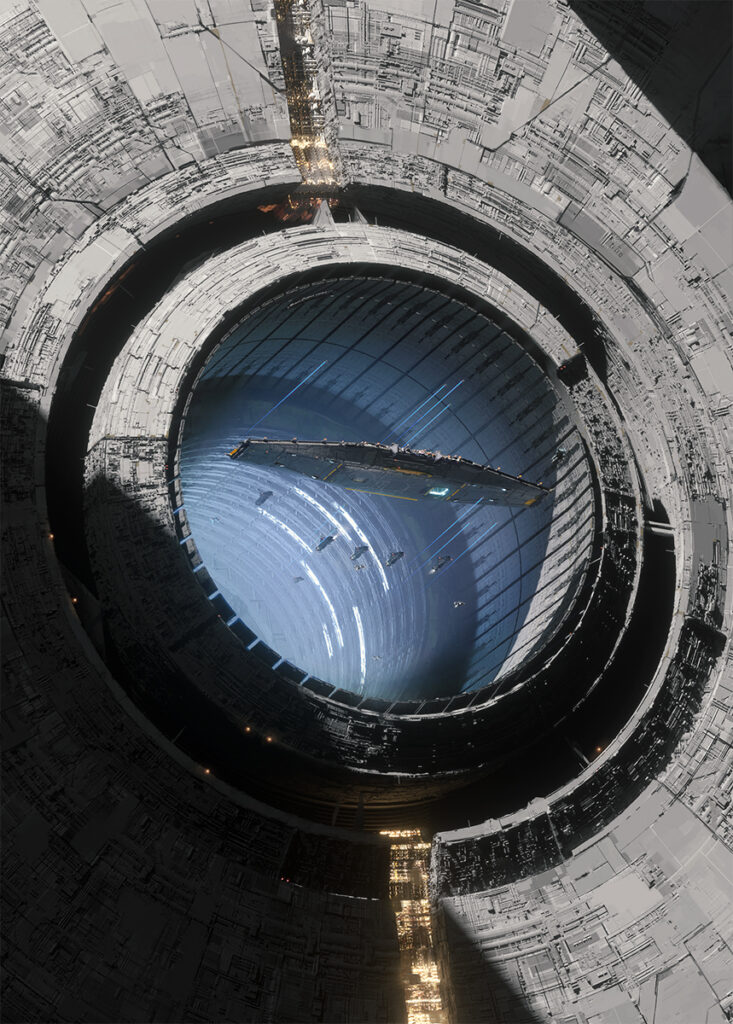

Since its inception in 1999, the Homeworld series’ hallmark has been its rich narrative, full of iconic moments across multiple titles that have stuck with fans for decades. As we prepare for the launch of Homeworld 3, the next chapter in this GOTY-winning sci-fi RTS series, we’re thrilled to interview Gearbox Managing Director of Narrative Writing Lin Joyce. Below, she talks about her role in shaping this new entry’s campaign as well as her responsibility overall within the framework of storytelling here at Gearbox.

What got you interested in Narrative Design and Writing in general?

I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t interested in writing. Before I could read, before I even went to school and learned how to draw letters (let alone make words with them) I was pretending to write books just by scribbling on paper and drawing pictures. There was always something magical about how words could unlock entire worlds, and I’ve always wanted to be able to create that kind of magic.

My love for Narrative Design took a little longer to flourish, and it’s possibly too jumbled a journey to untangle here, but I can say that it comes from a combination of interests: narratology (the study of narrative structures, themes, conventions, etc.), social agency theory, literature, theater, and game design. Many of the issues and criticisms against games, especially “story” games, were old criticisms applied to a new medium. As a scholar, I wanted to take a closer look at how older mediums grew, altered, or changed as a result of these criticisms and see if any of the same tactics could be applied to games. That investigation ended up leading me to a PhD in Narrative System Design. And while my focus of study changed over time, I’ve been thinking about storytelling in games ever since.

What draws you to Homeworld? Are there any themes or specific narratives within the franchise you treasure more than the rest?

The Homeworld franchise has so many good themes, and many of them are buried in the richly intricate concept that gives the franchise its name. There’s so much bound up in the idea of a “Homeworld” – legacy, heritage, identity, loyalty, and family, just to name a few. And within this franchise, each of those themes is complicated by the circumstances of displacement, technology, war, and prophecy. Having such rich themes at your disposal and then placing them in an expansive universe complete with space travel makes for a storyteller’s delight.

Why is conflict necessary in a story? Can a good story exist without conflict?

My stance is that stories require change. When we talk about conflict, we are talking about the catalyst that leads to change. So, when I am brainstorming, I don’t ask “what’s the conflict?” I ask “what does this person want?” “What challenge must they overcome to get it?” “And how does succeeding or failing alter them?” In other words, I’m trying to define their arc. Sometimes that arc is subtle. Sometimes it’s dramatic. And then sometimes the character doesn’t change at all, but their lack of change or resistance to change is what becomes compelling. Either external or internal forces are acting on the characters, or characters are acting on internal or external forces. It’s easiest to sum that up as “conflict,” but the important thing about conflict is how your characters sit in it, handle it, and emerge from it.

How do you balance finding new stories to tell within an established IP like Homeworld while also being respectful and paying homage to its past?

Once a story is shared, it belongs to the collective. It becomes a cultural artifact. And over time, our shared and collective memory of the story subtly shifts. We’ll start to remember the idea of the artifact more than its specifics. So, when we are lucky enough to get to be the custodians of a beloved IP, it’s important to balance two things: the true and factual story as told, and the remembered story.

So, when I come to an established franchise like Homeworld, I consider a couple of things: If I asked people to tell me the story of Homeworld, how would they tell it? And next I ask myself: what do people love about Homeworld? What I’m searching for is what has endured. What are the pillars and touchpoints that define the IP for the audience? If we can identify those things and honor them, then we are being the best custodians we can be for the IP.

As it happens, the Homeworld universe is also incredibly robust and provides nearly limitless opportunities to expand, explore, and tell new stories while honoring the elements of the universe fans love most. For me in particular, I am captivated by the themes of “place” and “movement” within the Homeworld universe. While these two themes feel at odds with one another, I think most people understand what it is to yearn for something different while also fearing change. Who we are trying to become is often stymied by who we are or who we used to be. It’s a challenge many characters, Kiith, and even planets in Homeworld are dealing with, each in a unique way.

Are there any characters in Homeworld 3 you are especially proud of helping shape?

The relationship between Imogen and Isaac was especially rewarding to work on. Imogen is a S’Jet, and in the Age of S’Jet, that comes with quite a bit of baggage and expectation. Imogen must bear the weight of other people’s expectations of her and the constant comparisons between her and Karan S’Jet. And while it’s true that Imogen is a S’Jet and a brilliant scientific mind, there’s more to her than those things. Her own belief systems, her moral compass, her dreams for her future, they all exist in spite of the expectations and plans others make for her. So when Imogen is called to duty, when she is asked to step into a role she never really wanted, she has to try to keep herself in focus. She has to hold onto what makes her Imogen while also being a S’Jet.

Isaac doesn’t make that easy for Imogen. Isaac isn’t in the business of making things easy for anyone, really. Isaac’s life is defined by rules, by a sense of duty. Where Imogen struggled under the expectations of others, Isaac thrives. As a Paktu, Isaac understands that rules and protocol are essential to survival. Isaac also understands that one must often sacrifice to ensure the survival of the many. He is a pragmatic realist, and his long military experience has given him ample reason to be. When he meets Imogen, he sees someone who lacks experience. He sees an idealist. He sees a scientist. He sees someone who is really going to push his buttons. In Isaac, Imogen sees another person trying to weigh and measure her worth. They are not natural friends, nor is there established trust between them, but they have a shared mission. A mission they both believe in. How to accomplish the mission, on the other hand…

What do you see as the most rewarding part of your work in storytelling?

When you are a storyteller in games, you are never telling a story alone. You are always storytelling in collaboration with others. That’s both the ultimate challenge and the ultimate reward. You must work together to create a harmonious experience for the player. The words the scriptwriter puts down on the page have to work in harmony with the game design and systems, the art, the sound, the animations, and so on. No idea can exist on its own. It has to be supported by other teams and departments and creatives. The ideas of one have to be supported by all. It’s constant discussion and iteration, but when it all comes together and it works, there is nothing quite like it.